Rocky Mountain post-fire regeneration

US Rocky Mountains

Are recent wildfires followed by the same level of tree regeneration as in the late 20th century?

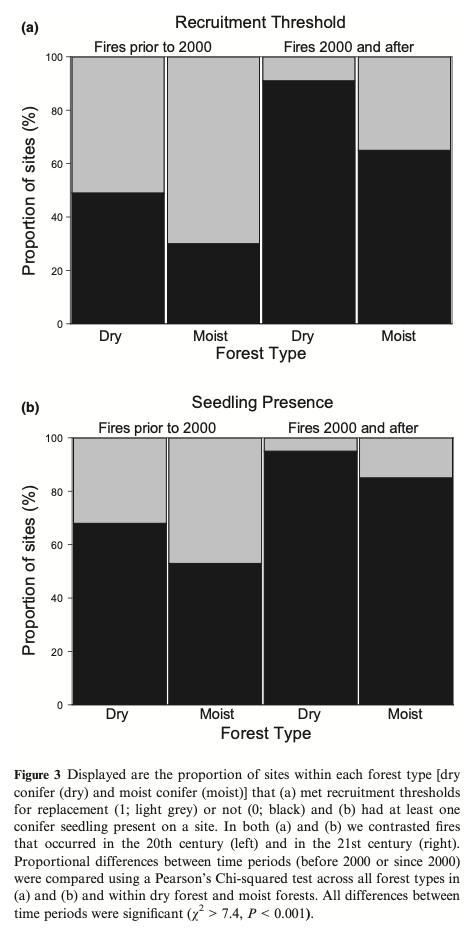

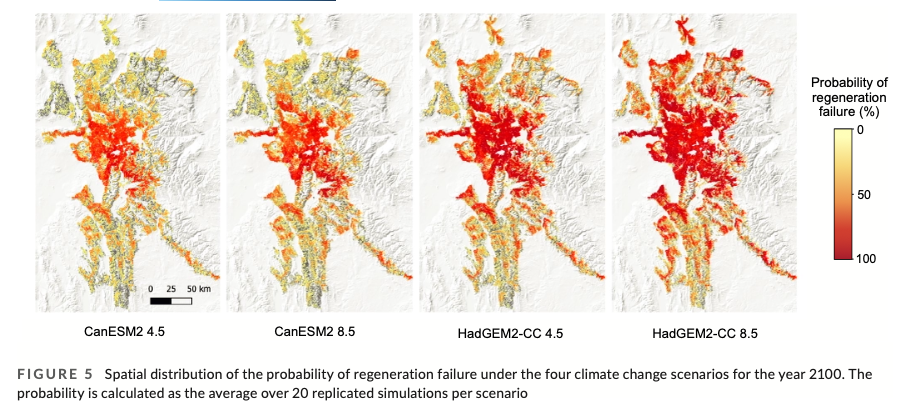

- Across 1485 sites burned in 52 wildfires, post-fire conifer seedling densities were often lower in 2000–2015 than in 1985–1999.

- Sites at the warm, dry edge of species' ranges showed the highest probability of regeneration failure.

- Warmer, drier post-fire conditions are already pushing some forests beyond their historical resilience.